Innovations in Theater

While being true to the spirit of his mentor, Ricky Abad pushed the Tinio agenda of Filipinization further by expanding from the mere use of a Pilipino translation to alterations in concept, time period, setting, and production style. He did so with the translations of Rolando Tinio, the set designs of future National Artist Salvador Bernal, and the choreographic, musical and technical genius of colleagues in the performing arts in hand. In making these connections, Ricky added a cosmopolitan quality to the repertoire, a quality that offered an opportunity to work on the international stage. It also fused the Ateneo theater of the pre-war and early post-war years, that of Fr. Henry Irwin, S.J. and Rolando Tinio, with the nationalist theater of the martial law years. Midsummer/Pangarap was followed by, among others, The Taming of the Shrew/Ang Pagpapaamo sa Maldita (2001), the epic Lam-ang (2004), and the sarsuwela, Walang Sugat (2010).

Ricky’s innovation in theater, here and elsewhere, was the localization of Shakespeare: the playwright’s words, yes, but presented with a Filipino and Asian sensibility. He intellectualized Shakespeare in order to explain him for, and not, to Filipinos. He was much appreciated abroad by colleagues for his work on decolonizing Shakespeare. Because he saw the playwright in a new light–by infusing him with a local sensibility–other countries also began to see Shakespeare through their own lenses. His legacy lives on in such places as India, Vietnam, Segovia, Minsk, Malaysia, Subic, Bohol.

His work was not merely performative; it also became academic. An invitation to become a fellow of the Salzburg Festival on Shakespeare (2001) fueled his desire to pursue further the localization of the playwright. Two invitations, from University of Singapore and Brown University, to present papers based on his staging of The Taming of the Shrew, as well as a journal article on it in The Drama Review (one of several publications written about his Shakespearean productions), launched his reputation as an international director and placed Ateneo theater on the international scene for the first time.

The turn toward the intercultural or more precisely, the interweaving of different cultures in a theatrical production, has been Ricky Abad’s lasting and distinctive contribution as a Filipino theater artist. “The interweaving style”, in Ricky’s words,

reflects an understanding of national identity that is plural, open, evolving, and inclusive. The question is not so much what the play or author says, but what the classic text says about the present. In practice, it means listening to other cultures, voices, or performing traditions, and after finding an insight, build on that connection, manifesting the interaction between past and present in language, set, costume, movement, and other elements that come from different source cultures.

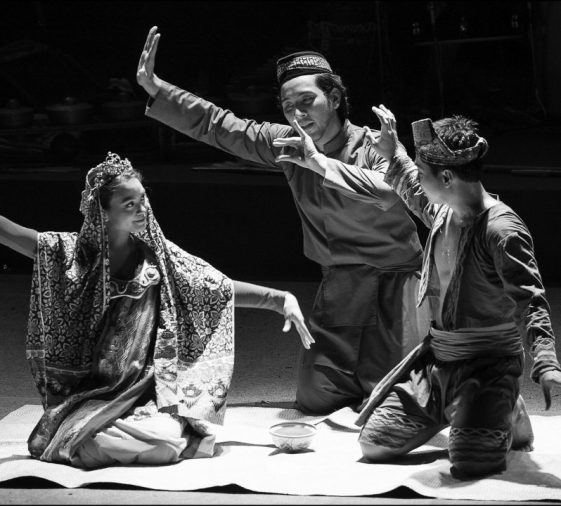

This “entanglement” of cultures was realized in Ricky Abad’s Sintang Dalisay, an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet in an imaginary Muslim setting, that deployed the igal, the dance of the Sama Bajau, as the movement and overall motif:

The intercultural premise of Sintang Dalisay is that a foreign work, like the original texts of the komedya, sarsuwela, or the American-based bodabil can become a new local work, the ‘third space’, owned and developed by local sources. How is this possible? One path lies in appropriating, or seizing, the foreign work so that it becomes one’s own. Sintang Dalisay does this through the relative ‘erasure’ of the original source material.

It partly uses Shakespeare’s text but relies heavily on a 19th century awit by the poet, G.K. Roke, entitled Ang Sintang Dalisay ni Romeo at Juliet. Live music commanded attention, and actors not only acted but danced, chanted, played traditional musical instruments in the tradition of village performers. Most important,

Sintang Dalisay heeded the lessons and opinions of master teachers from Tawi-Tawi to guide the production – a truly Muslim- Christian collaboration in practice.

Sintang Dalisay remains Ricky’s most successful and famous work. The production, first staged at the Ateneo de Manila in 2011, went on to have more than 70 performances, five of them in global cities – Shanghai, Minsk, Ha Noi, Penang and Kota Kinabalu — all to critical acclaim. Sintang Dalisay remains, at least for the moment, in the words of Dr. Judy Celine Ick, the foremost Filipino Shakespearean scholar, the “most successful Shakespearean production in Philippine history.” It was the Aliw Awards’ Best Play of the year and the Loyola School’s Project of the Year.

The interweaving process, of which Ricky Abad was an exemplary practitioner, championed diversity, hybridity and inclusivity:

Elements of the ‘other’ culture become sources of artistic expression and innovation, and the process of entanglement among cultures becomes an occasion for cultural groups involved in the production to collaborate with each other, thresh out differences, and reach a consensus. Seen this way, theater presents a model or an inspiration for exchange and dialogue among contending groups in the real world. Truly, it is a utopian vision of theater.

Implicit in this utopian vision was the quest for social transformation. The interweaving task was not merely an aesthetic effort, but an occasion to comment on the machinations of the dominant political apparatus. To Ricky Abad, the turn meant a postcolonial reading of the classical text, offering audiences a critique of the prevailing political order and a privileging of the local. Ricky’s plays departed from orthodox readings of classical texts; he pushed them forward and asked what can the playwright possibly mean today? He selected plays where characters strive to break down or resist obstacles that impede the practice of noble ideals, among them: freedom of speech in The Enemy of the People (2004), government cover-up in The Accidental Death of an Anarchist/ Ang Aksidenteng Kamatayan ng Isang Anarkista (2006), body shaming in Cyrano de Bergerac (1995), colonial oppression and “benevolent assimilation’’ in The Merchant of Venice/ Ang Negosyante ng Venecia (1999) and Taming/ Pagpapaamo (2002), agrarian violence in Light in the Village/Ningning sa Silangan (1999), incompetent leaders in Don Juan (2003), and political independence in Kahapon, Ngayon at Bukas (1998), Walang Sugat (2010), and 2Bayani: Isang Rock Operang Alay kay Andres Bonifacio (1996, 2022). For Ricky and his cast and crew, theater was liberating and empowering, a “weapon of change.”

As Ricky’s work became internationally known, Ateneo’s connections to global theater multiplied. Ricky Abad’s achievements as a theater artist were amply recognized. His work in Tanghalang Ateneo earned him Best Moderator Awards in 1991 and 1997, honors from the Ateneo for Outstanding Contribution to the Humanities in 2009, citations in

theater festivals held in Belarus (2013) and Vietnam (2016), and triple triumphs as Best Director in the Aliw Awards which quali�ied him to enter the Aliw Hall of Fame in 2017. He would later receive the Golden Leaf Award for Theater Arts Education and the Natatanging Gintong Parangal Bilang Pinakamahusay na Alagad ng Sining sa Teatro from a national non- governmental organization. His engagement with international theater led him to become an International Guest Director at the National School of Drama in India, twice president of the Asia-Paci�ic Bond of Theater Schools (China), Executive Committee Member of the Asian Shakespeare Association (Taiwan), Advisory Board member of the International Association of Theatre Leaders (Romania), School Representative in the Network For Higher Education In the Performing Arts, UNESCO (China) and the Asian League for the Institutes for Art (Taiwan) and Philippine Representative in the International University Theater Association (Belgium).

His theater work also generated enough campus interest to witness the rise of two other theater groups, Entablado and Blue Repertory. The growing student demand for theater eventually led, in 2001, to a formal course of studies in Theater Arts under the then Fine Arts Program. Ricky was the founding Director of the Program— now the Department of Fine Arts. Many of his students as well as members of his theater company now serve as members of the theater faculty or as teachers in the Loyola Schools and other units of the university. Several are active in professional theater, spreading the Magis of the performing arts and continuing his vision of theater as an instrument for social and personal change.